Have you ever wondered what it was like to go to school 50 years ago? Inspired by this recent time capsule recovery at a Vancouver elementary school, we browsed our 1969 textbooks to see what elementary school was like the year that Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, Woodstock was all the rage, and Sesame Street made its official debut!

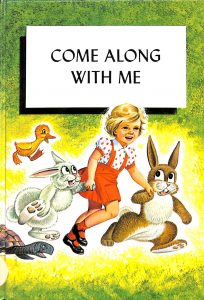

“Come Along With Me” was one of the many English readers assigned collectively to junior division grades.

On September 2nd, 1969, thousands of Ontario school children bid the “Summer of ’69” farewell and returned to the familiar hallways of their local elementary schools. According to the 1969 Circular 14 document (the Ontario government’s annual publication listing authorized textbooks grades K-12), the 1969-1970 school year saw a continuing trend of assigning multipurpose reading materials across grade levels. Whereas in years past, the Ontario Ministry of Education approved a specific textbook for each grade subject, educators were now beginning to acknowledge that individual students read at different reading levels regardless of their age and assigned grade level. Therefore, the Ministry began assigning a wide range of books and instructional materials for readers in Grades 1-6 (known as the Junior Division), leaving it up to teachers to determine which books best suited the needs of their students.

As such, teachers could choose from a wide range of English reading materials in 1969. For beginner readers, texts such My First Book (1966) and Come Along With Me (1960) featured simple stories and poems about children and animals, relying on repetitive vocabulary, large-print font, and colourful illustrations to help readers identify new words. For more experienced readers, books such as It’s Story Time (1962) introduced past and future tenses as well as multi-part or chapter stories.

Meanwhile, more mature readers could browse anthologies with chapters from famous texts, such as this version of Robin Hood from “Happy Highways 4”.

At the higher grade levels, anthologies such as Happy Highways 4 compiled excerpts from classic children’s stories including The House at Pooh Corner, Robin Hood, Through the Looking Glass, and Gulliver’s Travels (1962).

Building on the individual experience of the learner, educational psychologists such as Jerome Bruner, Jean Piaget, and Seymour Papert were meanwhile making advancements in the study of cognitive psychology for young children. By the start of the 1969 school year, “discovery learning” (referred to as “learning through discovery” in Circular 14) played a prominent role in the selection of subject textbooks; through discovery learning, educators concluded that children are likely to draw on past and present experiences to solve problems.

Discovery learning encouraged children to learn through real-life examples, such as practicing addition by purchasing school lunch.

For Grade 3 mathematics, the textbook Patterns in Arithmetic: 3 (1964) exemplified discovery learning by modelling questions after real-life experiences, such as asking students to count Canadian coins and to practice buying school lunch with a set amount of change. In the social studies curriculum, the Grades 4-6 book We Live in Ontario (1957) introduced topics such as population, culture studies, and climate through Ontario-centered examples.

To view pages from these textbooks and more, stop by the Ontario Historical Education Collections display case on the OISE Library ground floor. To learn more about Ontario’s government approved textbooks from 1969 onward, you can also browse digitized versions of Circular 14 at the Internet Archive.