For some 40 years, pupils in remote parts of northern Ontario attended some very unusual schools. Instead of going to the schools, these railway car schools came to them!

Until the 1920s, children living in northern Ontario often lived in settlements that were too small or too temporary for the construction of a regular school to be practical. As many as 75% were the children of railway employees, who were posted along the rail lines to maintain them. Other affected children were those whose parents did hunting, trapping, and forestry work. Once a permanent settlement had 12 pupils, the Department of Education would build a regular school in the community; however, until then, pupils had to rely on correspondence courses, with mixed results.

In 1926, the Ontario government conducted a two-car pilot run of the railway car schools. The rail cars were donated by the Canadian National Railway and the Canadian Pacific Railway and were converted into schools by the Ministry of Education. Teachers Walter H. McNally and Fred Sloman taught 82 children during this pilot run, stopping at 14 points along two rail lines. Of these children, 57 had never before attended school, and only 4 spoke English.

The railway school cars were an immediate success. During the two-year pilot run, these school cars had 100% attendance and the children attending them progressed rapidly, completing on average three weeks of schoolwork every week. Following the success of the pilot run, the railway car school program was expanded.

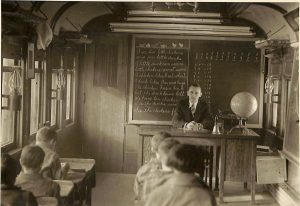

Two new rail cars were added in 1928, with an additional two in 1935, and one in 1938. At its peak in the 1940s, the Department of Education operated seven railway car schools serving over 200 pupils, with four cars operating on Canadian National Railway lines, two cars on Canadian Pacific Railway lines, and one car operating on the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway.

Each railway car school served 5 or 6 settlements and travelled about 150 miles each month. The school cars would stop at each point of call for 4 to 8 days, and the teacher would assign pupils homework to complete between calls. Although the railway school cars were not limited to a specific set of stops and would change location as the settlements changed, many children nonetheless travelled great distances by foot, horse, snowshoe, or even canoe to meet the school car.

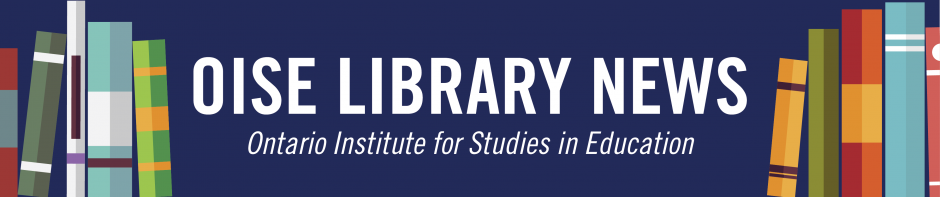

The railway school cars contained a school room as well as living quarters for the teacher and his family. The schoolroom was equipped with two blackboards, roll-down maps, a globe, desks, school books and general supplies, and a small lending library with titles for both children and adults. The railway car schools would also open night schools for their pupils’ parents, teaching reading, writing, and math.

Many of these parents did not speak English and could not read. For railway employees, these night classes offered them the opportunity for advancement in the rail company, as they could now perform functions such as writing a train order.

As the number of pupils attending the railway car schools decreased, so too did the number of railway school cars in operation. Ontario’s last railway car school closed in 1967.

The railway school car resources here at the OISE Library include correspondence, contracts, newspaper and magazine articles, and a great many photographs. A selection of photographs and other documents will be on display in the glass table on the ground floor of the OISE Library through the month of January.