Using Drama to Support Science Education

Student attitudes toward science can be influenced by emotions associated with all aspects of their various life experiences. Teachers can use transdisciplinary approaches that support student engagement by introducing students to the nature of science in emotionally connected ways.

Below, we detail four pedagogical strategies that use drama and discussions in science classrooms to explore students’ everyday encounters with science. The strategies engage the body and the emotions of the students so that they can express their feelings about science, providing the teacher with insights into students’ understandings about the nature of science. The first two strategies would be particularly effective at the start of a science course.

Strategy #1 - Nature of Science Statement Sorting Task

45-60 minutes

To reveal students’ cognitive understandings about the nature of science

This strategy engages students in conversation about the nature of science by providing them with the 15 statements listed below. Working individually, students sort the statements into four categories: strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree. Students then identify the statements that represent their two strongest points of agreement and disagreement, and engage in small group discussions about their decision-making. Eventually, the teacher can facilitate a whole class discussion about the array of thoughts about the nature of science.

Statements for the sorting task

- Scientific rules come from direct observations

- Good science relies on experiments

- Science is unbiased

- There is a sequence that should be followed when doing a scientific investigation

- Everyone agrees with scientific facts

- There is no place for culture or beliefs in science

- Scientists have strong gut feelings about the problems they tackle

- Scientific theories are just as good as laws

- Some things in life just don’t have answers

- Scientific laws don’t change

- Scientists are sometimes unsure about their conclusions

- Science is the best way to explain how the world works

- Science is based on interpreting observations

- School science is a snapshot of real science

- The best science is done in groups, not individually

Whole class discussion

The statement sorting patterns of all students can be pooled and converted into a bar chart or percentage breakdown that indicates the collective level of agreement and disagreement with each statement. The teacher can then guide students through a discussion of the various responses. The teacher should encourage students to exchange insights, pose questions, and draw from personal experiences.

Finally, the teacher can present the responses that are conventionally accepted in scientific circles, and may assign a reflective writing task to assess the progression of students’ comprehension.

Leading questions

“Why do you think a person might feel this way?”

“Why might others agree or disagree with the way you see science?”

Strategy #2 - Personification of Science

45-60 minutes

To uncover students’ emotional attitudes toward science

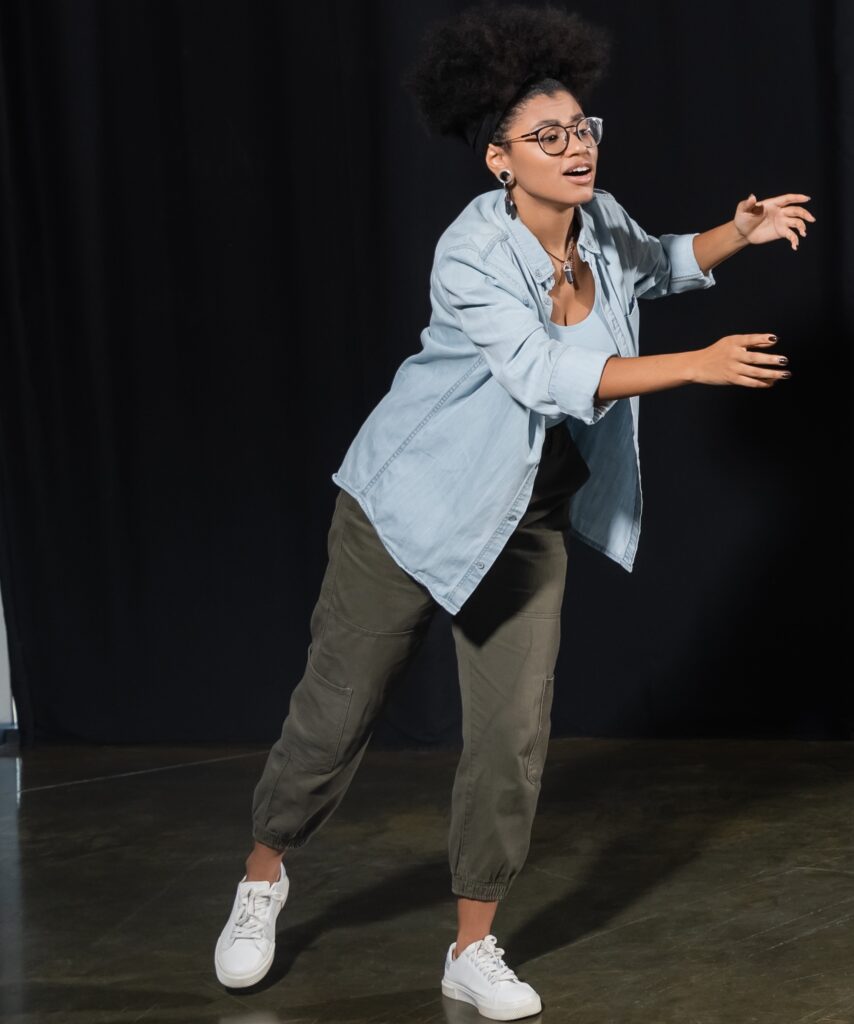

This strategy prompts students to reflect on their own relationship and experiences with science. Working in pairs, students are asked to create a “freeze-frame” depiction (tableau), similar to the mannequin challenge that was popular during the last decade, to represent the relationship between Science and Student.

They are asked to reflect on two questions:

- What is the relationship between science and the science student?

- If science were a person, how would science and the student interact?

Following each tableau presentation, a discussion within the class offers validation or counter-stories, based on students’ experiences with science.

Preparing the tableaux

Working in pairs, students have 10 minutes to choose the kind of relationship they would like to depict between Science and Student in their tableau.

To gain insights into students’ personal perspectives, the teacher circulates as students prepare, asking questions such as, “Can you explain why a person would feel that way?” or “How did you come up with this?” At the end of the planning period, the whole class gathers to share the various tableaux.

Post-presentation discussion

Following each pair’s presentation, the teacher and peers discuss their various interpretations of the tableaux and offer validations or counter-stories based on their own experiences. The teacher guides the discussion to examine the reasons why people may feel the way they do about science and to explore what kinds of depictions are missing, generating possible explanations for these omissions.

Leading questions

“What counter-stories challenge this interpretation of the science/student relationship?”

Strategy #3 - Viewing or Enacting a Science-Themed Performance

30-45 minute + play length

To develop students’ understandings of the social context of science

This strategy is based on watching a science-themed play so that students can build understandings of the nature of science. Suitable plays would be those which address a scientific concept combined with a social or cultural storyline; this combination introduces the complexity of moral/ethical problem-solving that is often hidden when studying science. After watching the performance, students engage in post-performance discussions to analyze the nature of science from the perspectives of characters in the play.

Alternatives to local productions

Viewing a science-themed play depends on the local availability of plays and school/student resources to facilitate theater attendance. Alternative strategies include collaborating with the school drama teacher to explore options for science-themed drama activities or producing a whole school production of a science-based play.

By their very nature, most science-themed plays fit the complexity criteria described above, but teachers may find the Curtain Up website helpful when selecting a play, based on reviews and additional guidelines provided.

Post-play discussion

A class discussion can present students with opportunities to view aspects of the nature of science from the perspectives of characters in the play. Prompts to guide discussion are provided below. Students should be encouraged to present the evidence upon which their answers are based.

- Did anyone in the play illustrate adherence to a way of knowing outside of science?

- In the play, who demonstrated the most scientific approach to life?

- In what ways did the person/people identified above indicate that science is tentative?

- What evidence of creativity in science did you see in the play?

- How did the social context influence the science being explored in the play?

- Evaluate the rigor of the scientific methods being illustrated in the play.

Leading questions

“What do you think the characters in this play would have thought about the statements presented in Strategy 1?”

“What do you think persuades the various characters to commit to their positions?”

Strategy #4 - Creating Scenes Based on Student-Selected Scientific Issues

45-60 minutes

To illustrate the kinds of scientific issues that concern students and how these influence their views on the nature of science.

This strategy supports students in shaping their own ‘take’ on a contemporary scientific issue by scripting and presenting a short acting scene to the class. The scenes they create represent an extract from a larger storyline and include an “inciting incident”—an event that would propel the main character into the central problem of the story in a dramatic or life-changing way. Teachers can use the students’ scenes to guide conversations that illustrate or challenge any of the nature of science characteristics listed in Strategy 1, using the guiding questions provided in Strategy 3. As with the other strategies, students’ written reflections could be gathered by the teacher to support future lesson planning.

Preparing for the scenes

First, the class collectively generates a list of important contemporary scientific issues; these issues can have local or global impact, and can be general or specific to the topic of study. After creating the list, as a class, the students prioritize the issues and the top-ranking issues are then distributed as topics for small group work. In smaller groups, students then develop a short scene based on the issue assigned; the goal is to work toward an “inciting incident” (described above). Students have 20 to 30 minutes to rehearse in groups before presenting their scenes to the class.

Leading questions

“What would the character you represented have thought about the statements presented in Strategy #1?”

“What do you think persuades them to commit to their position?”

Publication

For details of the various drama activities described above, visit our publication “Using Drama to Uncover and Expand Student Understandings of the Nature of Science” published in The Science Teacher.