Happy Earth Day 2023 from the OISE Library!

This Earth Day, we bring attention to the importance of promoting sustainability, biodiversity, climate action, and justice through gardening, growing, and seed saving. We have recently refilled the OISE Library’s Seed Library with seeds for this 2023 growing season! The goal of the Seed Library is to build connections between University of Toronto students, researchers, faculty and staff members, and our environment. Please drop by the OISE Library to check out the Seed Library collection and pick up seeds to grow food, native plants, and flowers at home or in your community.

The list below provides samples of resources such, ebooks, videos, podcasts, and articles, about how to contribute to climate action and sustainable education through gardening and growing with these seeds. Happy gardening!

Getting Started

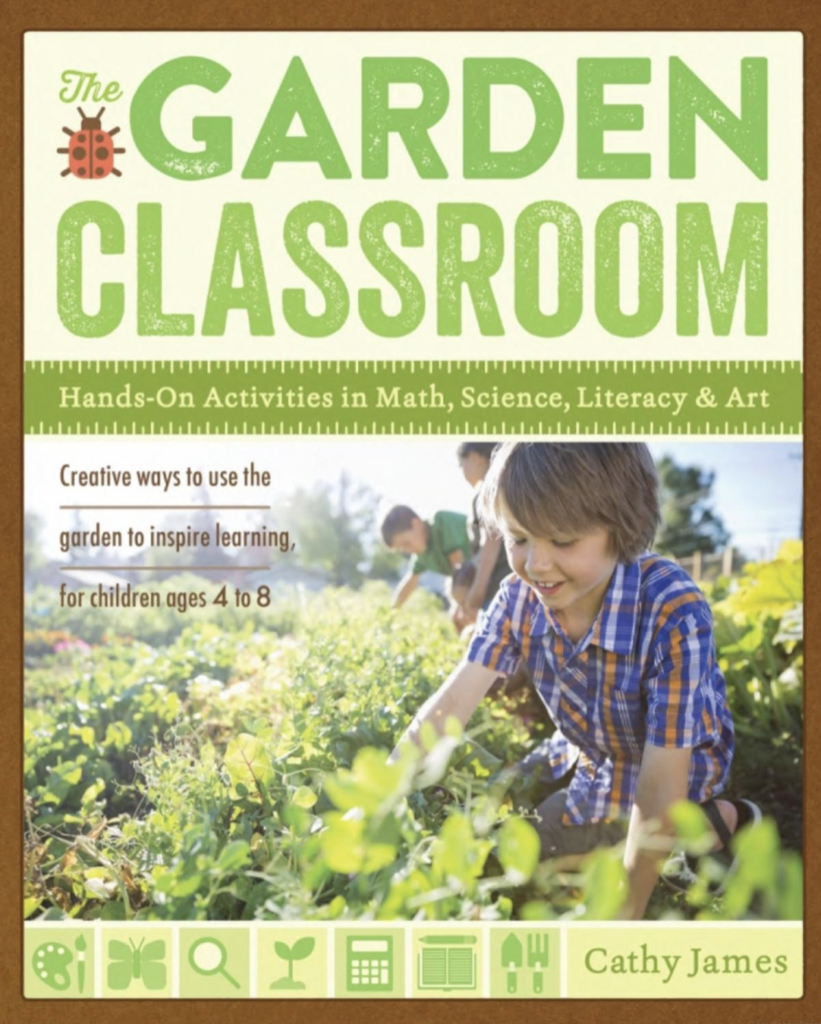

Book: The garden classroom: hands-on activities in math, science, literacy, and art, by Cathy James (2015).

Book: Ripe for Change: Garden-Based Learning in Schools, by Jane Hirschi (2015) provides a big-picture overview of the school garden movement in K-8 education.

eBook: Agrobiodiversity, School Gardens and Healthy Diets Promoting Biodiversity, Food and Sustainable Nutrition, edited by Danny Hunter, Emilita Monville-Oro, Bessie Burgos, Carmen Nyhria Roel, Blesilda M. Calub, Julian Gonsalves, Nina Lauridsen (2020).

Article (PDF): Why Forest Gardening for Children? Swedish Forest Garden Educators’ Ideas, Purposes, and Experiences, by Ellen Almers, Per Askerlund and Sofia Kjellström (2018).

Native Plants and Pollinators

Read:

Article (online): Native Plants and Seeds, Oh My!, by Lauren Pauley, Kendra Carlson, and Michele Koomen Hollingsworth (2016).

Article (online): Planting a Native Pollinator Garden Impacts the Ecological Literacy of Undergraduate Students, by Carrie Wells, Melissa Hatley and Jane Walsh (2021).

Workshop series (Open Access): Indigenous Knowledge and Pollinator Gardens, by Kelly Maracle (2021). This series of eight workshops is for teaching children in Grade 6 about the “importance of biodiversity, local community and Indigenous knowledge by creating pollinator gardens in the local community” (pg. 3). The workshops are connected to the Ontario curriculum.

Books (PDF): Bees of Toronto: a guide to their remarkable world, by the City of Toronto (2016), and the Toronto Pollinator Protection Strategy, by the City of Toronto (2018).

Article (online): Learning about Culture and Sustainable Harvesting of Native Plants: Garden-Based Teaching Can Foster Appreciation of Indigenous Knowledge by Eileen Merritt, Alex Peterson, Stacy Evans and Sallie Marston (2021).

Listen:

Podcast: What the f*** is biodiversity? Episode 9: Native bees with Dr. Sheila Colla, is about the important work of native bees in Canada and why they’re so critical for the environment and our food systems. Dr. Colla also shares suggestions about how we can help support these important pollinators.

Classroom Resources:

Lesson plan Elementary/Middle (PDF): Pollinator Power, by Glenda Clayton (2019) published at Resources for Rethinking.

Lesson plan Elementary (PDF): Monarch Butterfly, by Glenda Clayton (2021) published at Resources for Rethinking.

Article and lesson plan High School (online): “Promoting Biodiversity Through Urban Greenspaces”, by Michelle Loh, from the September/October 2021 issue of The Science Teacher.

Lesson plan Elementary/Middle (PDF): Creating a Three Sisters Garden, by Kids Gardening Organization (2002), allows students to investigate the Indigenous tradition of planting beans, corn and squash together, know as the “Three Sisters”.

Food Justice and Urban Gardening

Read:

Article (online): Growing ‘good food’: urban gardens, culturally acceptable produce and food security, by Lucy Diekmann, Leslie Gray and Gregory Baker (2020).

Article (online): Cultivating Positive Youth Development, Critical Consciousness, and Authentic Care in Urban Environmental Education, by Jesse Delia and Marianne E Krasny (2018).

eBook: Urban Gardening as Politics, edited by Chiara Tornaghi and Chiara Certomà (2019).

Master of Arts Thesis, OISE (online): Teach Me About Your Garden: Indigenous Youth Food Sovereignty in Tkaronto, by Diane Andrea Hill (2021).

Watch and Listen:

Film (DVD): Growing Cities, 2014. From rooftop farmers to backyard beekeepers, Americans are growing food like never before. Growing Cities tells the inspiring stories of these intrepid urban farmers, innovators, and everyday city-dwellers who are challenging the way this country grows and distributes its food. From those growing food in backyards to make ends meet to educators teaching kids to eat healthier, urban farmers are harvesting a whole lot more than simply good food.

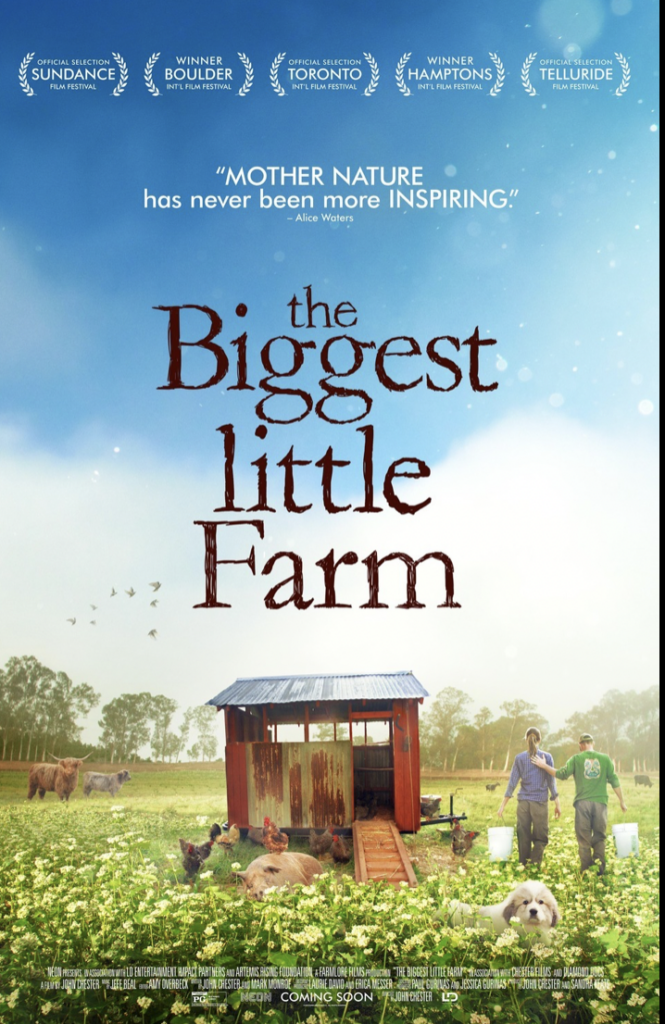

Film (streaming video): The Biggest Little Farm, 2018, follows a couple through their successes and failures as they attempt to develop a sustainable farm on 200 acres outside of Los Angeles, California. The film documents their successes and failures over the years as they work the desolate and difficult landscape.

Building Our Roots Podcast: Episode 4 – Sharing Seeds and Growing Community: Connection, Kin, and Culture. This podcast is a conversation about the Mississauga Youth Seed Library (MYSL). The project emerged from the Young Urban Growers program run by local environmental organization Ecosource, and seeks to support local food systems, build seed saving literacy. Hosted and edited by Emiko Newman and Megan Pham-Quan.

Film (streaming video): A Crack in the Pavement: Growing Dreams, by Jane Churchill & Gwynne Basen

(2000) from the National Film Board, is a two-part series that explores examples of children, teachers and parents across Canada making positive changes in their communities by working together to green their school grounds.

Please drop by the ground floor of the OISE Library to visit our seed library! For more help locating resources related to seed libraries, feel free to contact us!

- By email: oise.library@utoronto.ca

- At our Drop-in Virtual Reference Hours

- Online chat: U of T’s “Ask a Librarian” online reference service