This month we’re showcasing Canadian history textbooks across the years! On display inside the glass table on the ground floor of the library, you will find a selection of textbooks from nearly every decade since 1867.

In early Ontario schools, the purpose of history lessons was “to arouse in the pupil an interest in historical characters and events, to give him a knowledge of his civil rights and duties, to stimulate a love of high ideals of conduct, and to enable him to appreciate the logical sequence of events” (Ontario Department of Education, Regulations, Courses of Study, and Examinations of the Public and Separate Schools, 1915). Teachers were advised that pupils should not be confused by unnecessary details, nor should they be require to memorise notes – because forcing pupils to memorise notes would foster a dislike of history.

In early Ontario schools, the purpose of history lessons was “to arouse in the pupil an interest in historical characters and events, to give him a knowledge of his civil rights and duties, to stimulate a love of high ideals of conduct, and to enable him to appreciate the logical sequence of events” (Ontario Department of Education, Regulations, Courses of Study, and Examinations of the Public and Separate Schools, 1915). Teachers were advised that pupils should not be confused by unnecessary details, nor should they be require to memorise notes – because forcing pupils to memorise notes would foster a dislike of history.

Pupils in early Ontario schools did not only study Canadian history – British history was also a key component of early curricula. This is reflected in the earliest textbooks on display: A History of Canada and of the Other British Provinces in North America (1866, cover 1872) and the Public School History of England & Canada (1886). In fact, this second book is mostly about England – only the last quarter is about Canada!

By the 1900s, however, approved history textbooks placed more focus on Canadian history. Examples of textbooks from this period include: A Canadian History for Boys and Girls (1900), the Ontario High School History of Canada (1914), and the Ontario Public School History of Canada (1921).

By the 1900s, however, approved history textbooks placed more focus on Canadian history. Examples of textbooks from this period include: A Canadian History for Boys and Girls (1900), the Ontario High School History of Canada (1914), and the Ontario Public School History of Canada (1921).

British history nevertheless remained an important component of the history curriculum: Form III (grades 5 and 6) studied early Canadian history and British history up to the Norman conquest, while Forms IV (grades 7 and 8) and V (grades 9 and 10) studied major events in Canadian and British history, with an emphasis on recent history – which at the time meant the 1800s! Civics and government were covered in Form IV, and history was a mandatory subject of study through Form V.

Textbooks in these days were quite different from what we expect a school textbook to look like. They were text-heavy, with very few pictures, and did not include exercises or activities to engage pupils with the content. While some of these textbooks were used as early as elementary school, they more closely resemble something today’s students might expect to encounter in high school or university!

In 1937, the government of Ontario made significant changes to the curriculum. It was in 1937, for example, that students were placed into grades instead of forms. It was also in 1937 that Social Studies was introduced as a course of study: instead of teaching history and geography as separate subjects, they were now combined into a single class. Topics were presented to pupils gradually, starting with the home environment in grade 1 and expanding to the local community, the province, and finally to all of Canada in grade 6.

In 1937, the government of Ontario made significant changes to the curriculum. It was in 1937, for example, that students were placed into grades instead of forms. It was also in 1937 that Social Studies was introduced as a course of study: instead of teaching history and geography as separate subjects, they were now combined into a single class. Topics were presented to pupils gradually, starting with the home environment in grade 1 and expanding to the local community, the province, and finally to all of Canada in grade 6.

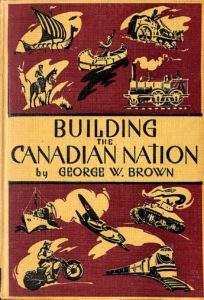

Textbooks were also changing. Covers, such as this one from Building the Canadian Nation (1942), were now being illustrated. While books from this period were still very text-heavy, they also included many more pictures than earlier books. Some, such as Canada: Then and Now (1954), were even beginning to use colour illustrations. Books from this period were also starting to engage students directly by including supplementary activities, end-of-chapter questions, and lists of suggested readings. Social studies curricula in the 1940s and 1950s also included guidance for teachers about the sorts of activities they could use in the classroom – these included activities such as creating picture books or making a “house” in the corner of the classroom.

In the 1970s, the curriculum again changed. While elementary school students continued to take social studies, students in grades 7-10 once again had two separate subjects: history and geography. History classes continued to focus almost exclusively on Canadian history; however, curricula now also explicitly acknowledged that ethnocentrism was often present in the study of history. It was understood that students of history would “discover something about attitudes and prejudices – [their] own and those of others” (Ontario Ministry of Education, History – Senior Division, 1970).

In the 1970s, the curriculum again changed. While elementary school students continued to take social studies, students in grades 7-10 once again had two separate subjects: history and geography. History classes continued to focus almost exclusively on Canadian history; however, curricula now also explicitly acknowledged that ethnocentrism was often present in the study of history. It was understood that students of history would “discover something about attitudes and prejudices – [their] own and those of others” (Ontario Ministry of Education, History – Senior Division, 1970).

By this time, textbooks were becoming larger in dimension – books such as Forming a Nation: The Story of Canada and Canadians (1977) and Flashback Canada (1987) were twice the size of early history textbooks! Textbooks from this period put still more effort into actively engaging students. By this point, the inclusion of activities, exercises, and end-of-chapter questions had become routine. Textbook material was also much more visual than before, including not only photographs and maps, but also diagrams and graphs.

This trend continued in recent textbooks, such as Canada: Understanding Your Past (1990) and Canada: A Nation Unfolding (2000). Modern Canadian history textbooks include summaries of a chapter’s material, pictures, maps, diagrams, and even comic strips to help convey concepts to students. As with textbooks from the second half of the 20th century, activities, exercises, and end-of-chapter questions are included – and have come to be an expected component of any school textbook. Modern textbooks are also more likely to acknowledge the darker parts of Canadian history, such as the history of residential schools.

This trend continued in recent textbooks, such as Canada: Understanding Your Past (1990) and Canada: A Nation Unfolding (2000). Modern Canadian history textbooks include summaries of a chapter’s material, pictures, maps, diagrams, and even comic strips to help convey concepts to students. As with textbooks from the second half of the 20th century, activities, exercises, and end-of-chapter questions are included – and have come to be an expected component of any school textbook. Modern textbooks are also more likely to acknowledge the darker parts of Canadian history, such as the history of residential schools.

These books will be on display in the glass table on the ground floor of the OISE Library through the end of July.

One Response to 150 Years of Canadian History Textbooks