During March, the Ontario Historical Education Collection is featuring a historical look at art education in Ontario.

From their earliest years, art education featured prominently in Ontario schools. In the early 1900s, art was a compulsory subject in public schools through Form V (Grade 10). Art as a subject was intended “to beautify and ennoble the pupil’s life by the sympathetic contemplation of Nature and of works of art, and to develop facility in the use if Art as a means of expression” (Regulations and Courses of Study and Examinations of the Public and Separate Schools, 1915).

From their earliest years, art education featured prominently in Ontario schools. In the early 1900s, art was a compulsory subject in public schools through Form V (Grade 10). Art as a subject was intended “to beautify and ennoble the pupil’s life by the sympathetic contemplation of Nature and of works of art, and to develop facility in the use if Art as a means of expression” (Regulations and Courses of Study and Examinations of the Public and Separate Schools, 1915).

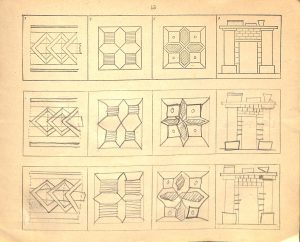

The Art curriculum in this period covered a wide range of activities, including the use of a variety of media such as pencils, charcoal, and watercolours, as well as techniques such as representative drawings of objects, patterns and ornamentation, landscapes, lettering, shading and colour, and perspective. Pupils also learned about famous artworks and architecture, and class visits to art galleries were encouraged. Although textbooks were not approved for use in the classroom past the mid-1800s, pupils used “blank books” such as the Public School Drawing Course or the High School Drawing Course for drawing exercises. A teacher’s manual for art instruction was, however, published by the Department of Education and school libraries were expected to have “suitable reference books” for art.

The Art curriculum in this period covered a wide range of activities, including the use of a variety of media such as pencils, charcoal, and watercolours, as well as techniques such as representative drawings of objects, patterns and ornamentation, landscapes, lettering, shading and colour, and perspective. Pupils also learned about famous artworks and architecture, and class visits to art galleries were encouraged. Although textbooks were not approved for use in the classroom past the mid-1800s, pupils used “blank books” such as the Public School Drawing Course or the High School Drawing Course for drawing exercises. A teacher’s manual for art instruction was, however, published by the Department of Education and school libraries were expected to have “suitable reference books” for art.

In the 1920s, less emphasis was placed on Art. A “minimum course” of study was required in all schools; however, the more enriched “supplementary” course was made optional. Art was also combined with Constructive Work into a single subject, which entailed a shift in focus and purpose to more practical endeavours than had previously been a part of art education. Other changes included an increased freedom granted to individual teachers about the content of the curriculum: specific topics of study could be selected according to the individual school’s situation. The Department of Education also stopped authorizing specific blank books for drawing – instead, teachers were permitted to make use of whichever blank books were available in their area.

In the 1920s, less emphasis was placed on Art. A “minimum course” of study was required in all schools; however, the more enriched “supplementary” course was made optional. Art was also combined with Constructive Work into a single subject, which entailed a shift in focus and purpose to more practical endeavours than had previously been a part of art education. Other changes included an increased freedom granted to individual teachers about the content of the curriculum: specific topics of study could be selected according to the individual school’s situation. The Department of Education also stopped authorizing specific blank books for drawing – instead, teachers were permitted to make use of whichever blank books were available in their area.

In 1937, the Department of Education conducted a major overhaul of the public school curriculum and art took on a more prominent role in the classroom. A compulsory subject of study from grades 1 to 8, the curriculum recommended 30 minutes of art daily. Art activities were also intended to be integrated into the curriculum across all subjects and creativity was strongly encouraged: “Every effort should be made to encourage the child in his art experiences and activities to select, observe, and record for himself, and to avoid reducing him to the position of merely doing what he is told. The sense of beauty and the desire and ability to express it are not likely to be developed by the dictation exercises sometimes called art lessons” (Programme of Studies for Grades I to VI of the Public and Separate Schools, 1937; emphasis in original).

In 1937, the Department of Education conducted a major overhaul of the public school curriculum and art took on a more prominent role in the classroom. A compulsory subject of study from grades 1 to 8, the curriculum recommended 30 minutes of art daily. Art activities were also intended to be integrated into the curriculum across all subjects and creativity was strongly encouraged: “Every effort should be made to encourage the child in his art experiences and activities to select, observe, and record for himself, and to avoid reducing him to the position of merely doing what he is told. The sense of beauty and the desire and ability to express it are not likely to be developed by the dictation exercises sometimes called art lessons” (Programme of Studies for Grades I to VI of the Public and Separate Schools, 1937; emphasis in original).

As time went on, the Department of Education began to pay more and more attention to teaching art in schools. In the 1950s, for example, a series of supplementary pamphlets about art education were published for teachers. The actual content of the curriculum itself, however, actually changed remarkably little over the years. The media may have changed – with students using tempera paints instead of watercolours, for example – but many of the activities, techniques, and goals remained consistent.

As time went on, the Department of Education began to pay more and more attention to teaching art in schools. In the 1950s, for example, a series of supplementary pamphlets about art education were published for teachers. The actual content of the curriculum itself, however, actually changed remarkably little over the years. The media may have changed – with students using tempera paints instead of watercolours, for example – but many of the activities, techniques, and goals remained consistent.

These materials will be on display in the glass table on the ground floor of the OISE Library through the month of March.