There’s no better time than December to cozy up with a mug of hot chocolate and a classic read! This month, the Ontario Historical Education Collection has gathered its books featuring two of the most well-recognized authors in English Literature; William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens. Follow along to learn how these two authors were taught in Ontario schools, and to discover how winter was celebrated in some of their most famous works.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) was a playwright and poet. He is celebrated across the world for his collection of famous collection of comedies, tragedies, and history plays including Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, Hamlet, Othello, Henry V and many more. In 1623, 36 of Shakespeare’s plays were published in a compilation commonly known as the First Folio. Half of the plays included in the First Folio had never been published before, meaning that many of Shakespeare’s works might have not survived otherwise.

Shakespeare’s works have been taught in Ontario schools since at least 1858. A peak into the General Catalogue for Books for Public School Libraries in Upper Canada (1857) indicates that anthologies such as William Hazlitt’s Shakespeare and Collier’s Shakespeare (both famous essayists and Shakespeare scholars) were selected by the Council of Public Instruction and were available for teachers and students to borrow. Though these books were available, they may not have been widely circulated. As school libraries were developed in proportion to school size, it was not uncommon for borrowing to be restricted in smaller schools. In some cases, if families had more than one member in the same school, librarians were instructed to “deliver not more than one book at a time for each family”, meaning students would have to patiently wait their turn to borrow books (or share them!).

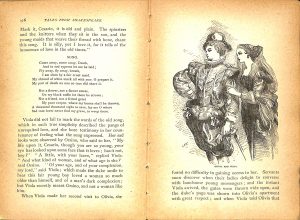

Anthologies such as Tales from Shakespeare (1932) organized plays into comedies, tragedies, and histories similar to the First Folio.

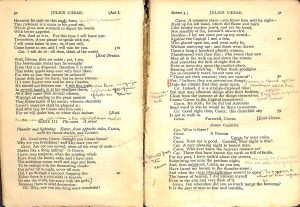

The oldest Shakespeare work in the Ontario Textbook Collection (OTC) – Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice by William J. Rolfe – dates from 1879. Through the 1930s, many plays preserved in the OTC were printed individually, often accompanied by illustrations, glossaries and editor’s notes. Hand-size copies of plays such as Hamlet, Love’s Labour’s Lost and The Taming of the Shrew might have been useful as portable copies for performance – like many students today, the former readers of these books were no strangers to underlining and annotating their speaking lines! By 1936, students in Grades 9-12 were expected to read at least one of Shakespeare’s plays as part of their English Literature course. Anthologies such as Tales from Shakespeare (1932) offered students a choice reading selections. By 1960, Shakespeare had become so synonymous with English and Drama studies that the Ministry of Education had to release a statement in its Grade 11 and 12 Courses of Study reminding teachers that no more than 25% the time allotted in a literature course should be spent on Shakespeare!

Twelfth Night, or What You Will, was one of the plays to be introduced in publication through the First Folio. Twelfth Night is a romantic comedy about a countess who falls for a lover dressed in disguise, and was first performed on February 2nd 1602 at the end of the Christmastide season. In early modern England, the Christmas season officially began with Christmas Eve, and ended with Epiphany Eve, or the Twelfth Night. The first recorded public performance of Twelfth Night was on February 2nd, 1602, at Candlemas, the official end of the Christmastide season in the church calendar. Though the play was likely performed in celebration of the holiday season, the actual content of the play has little to do with the time of year.

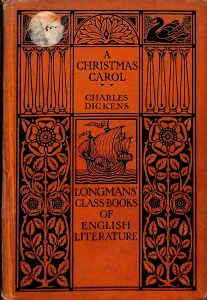

In fact, the Christmas holiday that is celebrated today most closely resembles the Christmas season of the Victorian era (mid 19th century to early 20th century). The Victorian Christmas holiday prioritized church and family togetherness, and festivities revolved around families and friends coming together to eat and drink. Charles Dickens‘ (1812-1870) A Christmas Carol, originally published as a short story in 1843, is still regarded today as a classic Christmas story, with many play performances, literary and film adaptations contributing to its long-lasting success. Despite its current popularity, many of the symbols of Christmas today – Christmas trees, carolers, and exchanging presents – were not in the original version, which instead prioritizes contributing to charity. Dickens followed A Christmas Carol with four other Christmas stories; The Chimes (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), The Battle of Life (1846), and The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain (1848).

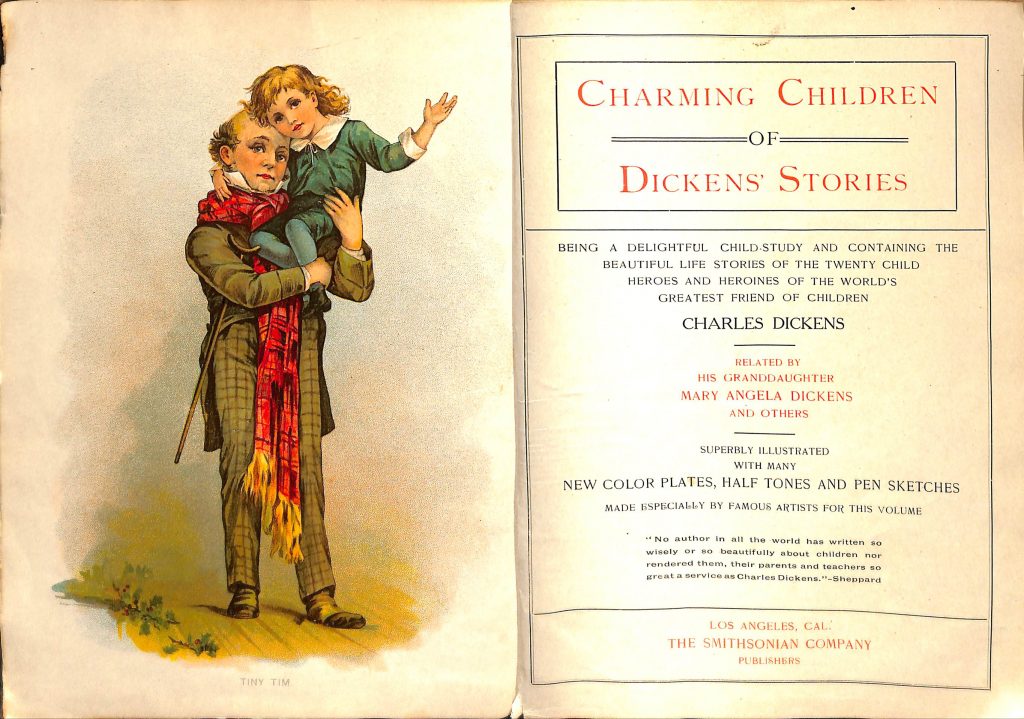

The Ontario curriculum introduced elementary readers to Dickens through anthologies such as Charming Children of Dickens’ Stories (1906), which featured abridged chapters and illustrations from tales such as The Old Curiosity Shop, A Christmas Carol, Dombey and Son and David Copperfield. Individual copies of A Christmas Carol (1907) and The Cricket on the Hearth (1920) were glossaries and readers notes were assigned for use in public and high schools throughout 1910s and 1920s. By the 1930s, curriculum documents for high school English courses indicated that teachers were required to teach one of Dickens’ novels to students in Grades 9 and 10, and another in Grade 11 and 12. Choices alternated between David Copperfield, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, and Oliver Twist.

To view the works of Shakespeare and Dickens available from our Ontario Textbook Collection, be sure to stop by the Ontario Historical Education Collection display case on the ground floor of OISE Library. To access the ground floor during construction, you can enter from the second floor and take the elevator or stairs.