Exploring Food Insecurity using Financial Literacy

Using mathematics to understand food insecurity highlights factors

that influence one’s ability to access food.

Due to the supply issues resulting from the pandemic, Ontarians have seen a rising cost of food and it looks as though it will continue for the foreseeable future1. In fact, the average family household of four will pay an extra $966 for food in 2022, according to the most recent edition of Canada’s Food Price Report2. The rising costs of food puts more households at risk of food insecurity.

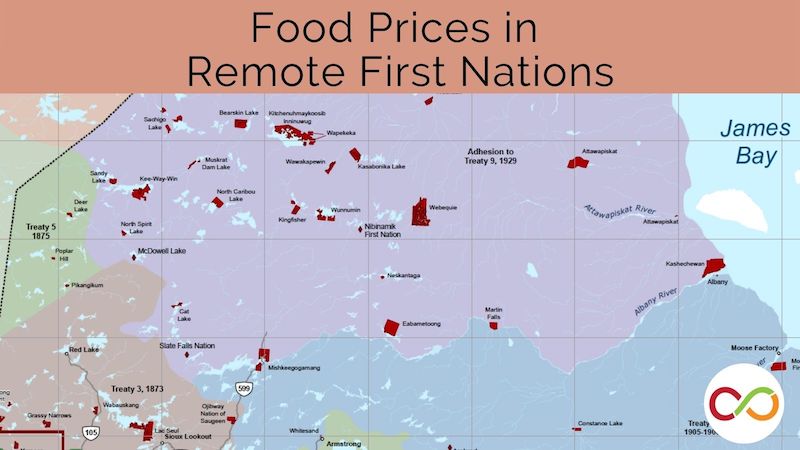

As I began researching why food prices vary, it became clear that remote communities, typically with high populations of Indigenous peoples, endure food prices that are even higher. Food insecurity rates are significantly higher in remote communities with no year-round road access to a service centre3. High food prices paired with income inequality puts households at even greater risk for food insecurity.

Using mathematics to understand food insecurity can concretely highlight factors that influence one’s ability to access food. It also provides a foundation to explore potential solutions. More specifically, teaching children about financial literacy can show students that there are financial implications tied to income, taxes, and even price discrepancies as they shop at the store.

Making concepts of financial literacy relevant to children

The new Ontario Math Curriculum4, revamped in 2020 to include the study of financial literacy in the elementary grades, includes learning about money concepts, financial management, and consumer and civic awareness. Before children experience responsibility for earning a stable income, buying groceries, and managing their own money, attempts to make money management relatable may be ineffective. Moreover, having students examine their own lives – say, by creating a budget for a week’s worth of groceries – may highlight socioeconomic differences among students’ families, potentially leaving students feeling uncomfortable.

A section of the Financial Literacy strand of the Ontario Math Curriculum focuses on consumer and civic awareness. It includes an expectation that students learn “different ways to distribute financial and other resources among individuals and organizations.” The costs of food is an excellent starting point for exploring the ways this essential resource is distributed, as well as the impact food insecurity has on lives. Food insecurity is “the inability to acquire or consume an adequate diet quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways, or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so,” as defined by the Government of Canada5. By looking at communities that experience food insecurity, students can learn about how money is transferred between people or organizations, along with the costs of transactions, taxes, budgeting, and the impact of subsidies.

To study food insecurity in remote First Nation communities, I have developed three lessons that focus on collecting, visualizing, and comparing food price data. Students will understand the basics of taxes, including how rates vary from item-to-item, and they will consider the influence geographical location has on the total cost of the item. They will determine for themselves whether solutions, such as subsidies, provide adequate support to make food accessible to Canadians living remotely in Northern Ontario.

Lesson 1: Comparing food prices

To launch an inquiry on food insecurity, one relevant starting point is to examine how the cost of food varies at the local level. Students begin by comparing the cost of food items from different Southern Ontario grocery stores. By collecting, recording, and comparing the price of food, children engage in curriculum expectations of data management, measurement, number sense, and, of course, financial literacy. Students begin to see that, even within kilometres, the costs of food can be very different. Most importantly, students build a foundation for examining the impact food cost discrepancies have on households.

Lesson 2: Food insecurity in remote Indigenous communities

As students investigate how geographical location influences food costs, they will also learn about the people who reside in these rural communities and recognize that remote communities are especially vulnerable to food insecurity. In Ontario, one in four First Nation communities is remote, which means the community is only accessible by air year-round or by ice road in the winter6. This poses a difficult challenge when ensuring those families have access to affordable food.

As a follow-up lesson to exploring food prices within Southern Ontario, students focus on a remote Indigenous community within Ontario, such as Attawapiskat. Students compare the average cost of everyday food items found in the Greater Toronto Area with Attawapiskat. Students will see the dramatic difference in food costs which leads to exploration around the causes and implications of high food prices. In addition, students learn about taxes and why different rates are applied to different food items. This creates an opportunity to address a common misunderstanding that Indigenous people are exempt from paying taxes.

Lesson 3: Subsidies: Do they alleviate food insecurity in remote Indigenous communities?

After exploring the difference between food prices in different regions, students turn their attention to what is being done to tackle food insecurity in these communities. One way the federal government supports remote Indigenous communities is through a subsidy program called Nutrition North7. Communities eligible for this program receive a subsidy on certain food items, such as vegetables but not frozen hamburgers. Thus, the prices shown from the grocery store in Attawapiskat are the prices after the subsidy has been applied. The subsidy of an item is calculated in dollars per kilogram. Students can apply their knowledge of measurement conversion by calculating the cost of an item without the subsidy applied. This way students can determine whether the subsidy truly makes food accessible.

While food insecurity is evident among many households, colonization and the trauma of residential schools has made Indigenous people more susceptible to income inequality, higher food prices, and thus, food insecurity. Despite these great challenges, Indigenous people continue to be resilient by regaining control of their culture, language, and land. Many Indigenous people harvest, hunt, and fish to provide food for their families and to share with their community. Other communities have started co-ops8 as a way to control businesses in their communities. By understanding financial management and money concepts, students are better positioned to examine ways to support Indigenous people and other households in overcoming food insecurity.

Food insecurity is a national problem

The issue of food insecurity is not unique to remote First Nations. Because food insecurity is closely linked to income, many households all over Canada experience food insecurity9. In addition, households can experience food insecurity on a spectrum. Households may be able to afford food one week, but not the next.

Donating to local food banks

592,308 adults and children accessed a food bank in Ontario between April 2020 and March 2021 – an increase of ten per cent over the last year and the largest single-year increase since 200910.

One of the best ways citizens can support households who are food insecure is by donating to local food banks. Visit www.feedontario.ca to find a local food bank near you.

References

- Jackson, Hannah (2022). Here’s a look at what’s going to cost more in 2022. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/business/here-s-a-look-at-what-s-going-to-cost-more-in-2022-1.5722156#:~:text=The%20report%2C%20released%20in%20early,five%20to%20seven%20per%20cent.

- Charlebois, Sylvain & gerhardt, alyssa & Somogyi, Simon & Kane, Mitchell & Keselj, Vlado & Music, Janet & Colombo, Stefanie & Jackson, Ethan & Taylor, Graham & Kenny, Tiff-Annie & Abebe, Gumataw & Rd, Jess & Corradini, Maria & Uys, Paul & Duren, Erna & Smyth, Stuart & Lassoued, Rim & Vercammen, James & Wiseman, Kelleen & Zhang, Meng. (2021). Canada’s Food Price Report 2022. 10.13140/RG.2.2.20726.52804.

- Chan, Laurie, Malek Batal, Tonio Sadik, Constantine Tikhonov, Harold Schwartz, Karen Fediuk, Amy Ing, Lesya Marushka, Kathleen Lindhorst, Lynn Barwin, Peter Berti, Kavita Singh and Olivier Receveur. 2019. FNFNES Final Report for Eight Assembly of First Nations Regions: Draft Comprehensive Technical Report. Assembly of First Nations, University of Ottawa, Université de Montréal.

- The Ontario Curriculum, Grades 1-8: Mathematics, 2020. Toronto: Ontario, Ministry of Education, 2020. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

- Household food insecurity in Canada: Overview. Government of Canada, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/household-food-insecurity-canada-overview.html. February 2022.

- In the spirit of reconciliation. Ontario Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, 2017, https://ontario.ca/document/spirit-reconciliation-ministry-indigenous-relations-and-reconciliation-first-10-years/indigenous-peoples-ontario#:~:text=Thunder%20Bay%20is%20the%20Census,non-Indigenous%20population%20in%20Ontario. February 2022.

- Nutrition North Canada. Ontario Government, 2016, https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca. February 2022.

- Arctic Co-operatives Limited. https://arctic-coop.com/index.php/about-arctic-co-ops/history/

- Tarasuk V, Mitchell A. (2020) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF).

- Hunger Report 2021: How the pandemic accelerated the income and affordability crisis in Ontario. Retrieved from: www.feedontario.ca.