Bringing Stories

into

Science Classrooms

Dr. Julie Comay explores how the inclusion of stories in science learning can create a bridge from the known to the unknown for students

READ AHEAD:

For all its riches, the dry abstractions and formal categories of western science can render the subject impenetrable and uninteresting for many students, detaching science from its vital roots in wonder, as well as from its pragmatic involvement in the concerns of everyday life. It has been suggested that the disconnect between school science and everyday knowledge may be especially glaring for children who grow up outside the Euro-Canadian mainstream, including Black and Indigenous students, whose under-representation in STEAM fields may in part reflect a clash between cultural ways of knowing. Glen Aikenhead (2001) at the University of Saskatchewan urges educators to not underestimate the extent of the cultural “border crossing” that faces many students as they enter school, especially in math and science.

As modern science diverges farther and farther from its roots in Indigenous thought, rich and complex modes of understanding and expression have been supplanted with the analytic elegance – and accompanying reductiveness – of the “scientific method,” beautifully illustrated in Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer. One cost of a curriculum based primarily in European Enlightenment principles has been the catastrophic erosion of our living, breathing relationship with the Earth; one remedy may be to restore to our children the possibilities of experiential learning in and upon the land (e.g., Natural Curiosity, 2nd Edition, 2017). Along with this, another fundamental way of knowing and relating to the world – the use of narrative – has also tended to be a casualty of the current science curriculum. While most cultures use narratives to teach children important facets of human existence and co-existence, stories are typically considered more incidental or irrelevant to the aims of science education.

Two modes of thought

Cognitive scientist Jerome Bruner (1986) stressed that science and narrative are radically distinct modes of thought that construe different worlds in different ways. He depicted science as a form of “paradigmatic” thinking that divides the world into mutually exclusive concepts and categories; it approaches “truth” through accurate observation and logical deduction. In contrast, narrative thought establishes lifelikeness, not truth, and broadly deals in human or human-like intentions and actions.

Consider language. Classic scientific writing aspires to pure communicative transparency. Its aim is to shed the murky trappings of subjectivity and unambiguously convey the truth of a matter. Narrative prose, on the other hand, remains firmly situated in the context of its telling, expressing a developing relationship between teller and listener – or writer and reader – in a text that can always be further unpacked. No telling (reading) is ever the last word. As a vehicle for both communication and reflection, a worthwhile story bears repeating in a way that a successful scientific account does not.

Yet both modes at heart set out to make sense of the world. Each calls for curiosity and imagination, hypothetical reasoning, and representation through modelling and analogy. Also crucial to both: precision in observation and description, sense-making and coherence-building, questioning, sequencing, causal thinking, perspective-shifting, the identification of patterns and anomalies. As we strive to make science more accessible, engaging, and relevant for the students we teach, we can exploit those commonalities as we recognize the potential of narrative to acculturate children into the foreign realm of science.

Getting scientists to consider the validity of indigenous knowledge is like swimming upstream in cold, cold water. They've been so conditioned to be skeptical of even the hardest of hard data that bending their minds toward theories that are verified without the expected graphs or equations is tough. Couple that with the unblinking assumption that science has cornered the market on truth and there's not much room for discussion.

Narrative: A bridge to scientific thinking

While children are immersed in stories from their earliest days, the formal ways of school science are less immediately intuitive. It is not surprising that a teacher may need to offer a hand as students grope to master the protocols and expectations of this less familiar kind of knowledge. Presenting information in narrative form has been shown to enhance memory, engagement, and cognitive understanding. Stories can help students traverse the gap between everyday ways of thinking and the decontextualized symbols and concepts of school science. A number of studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of simple science stories in cementing concepts for young children (e.g., Kelemen et al, 2014). It was even recently shown, somewhat counter-intuitively, that preschoolers learned scientific information better from fantastical stories that violated real-world physical or biological laws than from more reality-bound stories that conveyed the same information (Hopkins & Weisberg, 2021).

Commenting that “stories take us inside a child’s world, and their world is mathematically and scientifically alive”, Story Time STEM at the University of Washington offers narrative-based resources to support parents and teachers of young children exploring math and science concepts. The program’s creators note its potential to broaden views of science and increase diversity in STEAM areas.

Bringing stories into science learning offers students a bridge from the known to the unknown. Unlike scientific language that mostly functions within a specialized professional community, stories juxtapose and layer ordinary language in ways that reveal new meanings and interpretive possibilities. Infusing cultural dimensions into pedagogy, they offer a powerful teaching tool that can uniquely connect students with their learning, providing windows into a diversity of perspectives and ways of understanding. Stories invite listeners to both learn about new things and to feel them, providing a view of phenomena from within and without. A tree, for example, might be simultaneously grasped in its full singularity – from its own point of view, in a way – and as a universal exemplar suggesting other entities of its kind. Narrative language has the elasticity to encompass such a perspective shift.

Stories of scientists and science

Understanding how science works and what scientists do are critical to building scientific literacy. Life stories of scientists that show the human side of discovery are a natural vehicle for building connections between students’ everyday understanding and their scientific knowledge (Sharkawy, 2006; Korkmaz, 2011). Biographical accounts situate science in a cultural-historical framework, offer entry into the world of their subject, and often inspire the desire to make a mark in that world. Of course, the question of representation – who are the scientists? – is critical here, and the challenge for teachers is to select a range of biographies that are sufficiently diverse for all children to imagine themselves in the science world. Given numerous studies showing that representation in STEAM books is still overwhelmingly white and male, it may require some dedication to identify high quality books that broaden student conceptions of who belongs in science.

Another genre of non-fiction or hybrid science books places scientific information in a compelling narrative context. Wolf Island (Godkin, 1993; 2014) recounts the cascade of ecological disasters and subsequent restoration of balance following the departure and accidental return of a family of wolves from their island. This beautifully told and illustrated story is perfectly suited to its theme, which concerns the interconnections among living elements of the ecosystem.

A different kind of example is found in such books as The Pebble in my Pocket (Hooper, 1996; 2015), which starts from the perspective of a child discovering a pebble and takes us through the lengthy history of that particular stone to tell the geological story of the Earth. Narrative turns out to be the perfect form for conveying the natural history of our planet.

Finally, the pressing moral imperatives of environmental concerns and human rights may be most effectively conveyed to children through stories. We are Water Protectors (Lindstrom and Goade, 2020) tells a short, powerful story about critical issues of water rights facing First Nation communities in Canada. When a black snake threatens to poison her people’s water and destroy the Earth, a young girl takes action. The snake, of course, is a metaphor for the oil pipelines. Another story, Water (Vyam and Wolf, 2018), based on a traditional Gond fable, offers a cautionary tale about what happens to a village in India when a dam is proposed to benefit people in a faraway city.

Stories and Indigenous pedagogy

Indigenous peoples across the world have long understood the pedagogic power of stories. David Osorio, a teacher at the Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study Lab School and doctoral student who is currently researching the use of Indigenous children’s literature in land-based learning, speaks of his second graders:

“Using stories is one way I use two-eyed seeing [combining western and Indigenous knowledges] in the classroom, tapping into the strengths of Indigenous perspectives on the natural world. Children can digest these perspectives better when they’re communicated through a picture book. The images paint a certain picture, and the language is different from the language of a western science book; these books use the language that the science is rooted in. The kids really latch onto them because the Indigenous perspective brings in the emotional piece, the connection with the world outside.”

David stresses the ethical dimension of Indigenous stories that are rooted in the land. These traditional tales, often focusing on a problem in the community, reveal the human perspective as only one element amid a densely interwoven web of relationships. “When we take that [relational] perspective and connect it to being outdoors, we see how the fungi are connected to the roots and how the ants support the fungi that support the trees” and how we breathe in the oxygen from the trees, and so on. The capacity of narrative to reveal unexpected connections reflects the deep interconnectedness that is fundamental to ecological understanding.

Indigenous stories can play an essential role in broadening our science curriculum beyond colonial knowledge systems. Instead of emphasizing the detachment of the human observer from the natural world – as colonial science has historically done – narrative expresses and furthers our understanding of our own enmeshment in a complex relational web. Further, the capacity of narrative for indirectness – its ability to suggest deep truths rather than prescribe them – may create space for students to each make sense of the ethical/spiritual dimensions of an Indigenous telling from their own perspective, in their own particular context.

Indian people don’t really instruct their children, they story them. That is, not only tell them stories, but encourage them to hear and see the stories of the world around them.

The stories we tell … and how we tell them – are shaping the world of our children, of our grandchildren. We can reclaim and validate Anishinaabeg epistemological frameworks. Anishinaabeg stories are not supplementary; they are central. In reclaiming our stories, we are responding in concrete ways to recurrent calls to ‘Indigenize the academy’.

Indigenous stories are oral in their origins, and there is no substitute for the ability of oral storytelling to draw listeners into the world of the teller. Meaning will be immeasurably deepened through the continued wisdom and guiding presence of Indigenous knowledge-keepers and storytellers. Another sustained opportunity to bring Indigenous voices into classrooms can be found in the growing body of published picture books authored and illustrated by contemporary Indigenous writers and artists. Sharing an author’s biographical information and carefully situating the story in its cultural and geographical context help to clarify for listeners its rootedness in Indigenous experience and beliefs. For a teacher wondering where to begin, resources such as the FNESC Authentic First Peoples Resources (FNESC, 2016) offer detailed frameworks for selecting culturally appropriate books along with a vast list of annotated examples.

Another website, founded by Pueblo scholar Debbie Reese, offers a critical analysis of Indigenous children’s literature, though from an American perspective. In this video, Dr. Reece discusses what to consider when selecting excellent children’s books by Indigenous authors.

One group of researchers, who introduced a story-based science curriculum into Maori schools in New Zealand, wondered whether certain narrative genres were better suited to science contexts. They asked, “Can science stories be good stories? Or are stories inevitably ‘not proper science’?” Though all stories were told in the Maori language and designed to reflect local cultural practices, they found that those explicitly designed to convey science information tended to strike a “false note” and failed to fully engage students. Far more effective were traditional tellings that expressed Maori worldviews, such as a tale of warring mountains that results in the formation of a local river gorge, linking observable features of the landscape with story characters and events. The authors suggest that successfully using stories in science education requires a shift from conceiving of science as a fixed body of facts to viewing it as a way of thinking. Providing students with two knowledge systems (science and cultural narrative) then becomes “a resource, an asset… Children can learn about the different knowledge systems – how they work, what is important in them, and when and where they should be used.” (Gilbert, Hipkins & Cooper, 2005)

Indigenous cultural stories may also invite listeners to notice their surroundings differently. Educators in New South Wales, Australia, describe how intensive exposure to local Indigenous sky stories ignited in students a new kind of attentiveness to the movement of stars in the sky. Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous high schoolers were inspired “to articulate their own cultural sky stories and seek out further examples about the night sky. The cultural sky stories seemed to motivate students to observe the actual night sky in their own time.” This primed them for a series of investigations within the framework of western astronomy (Ruddell, Danaia & McKinnon, 2016).

Closer to home, the website Lessons from the Earth and Beyond offers a wealth of resources for bringing Indigenous knowledge systems into science classrooms. As part of an extensive array of curriculum-focused materials, stories are integral to each of three sections devoted to the Earth, Water, and Sky. Among the site’s riches are videos featuring Anishinaabeg storyteller Isaac Murdoch and Cree astronomer and storyteller Wilfred Buck (see his website, Acawuskwun.com, and also One Sky, Many Astronomies).

In these times, whatever our differences of approach and worldview, western and Indigenous sciences are mostly in agreement about the urgent need to reverse the course of a planet in crisis. Though it may have a lot to answer for, the accumulated knowledge of western science also has much to offer, as do time-tested Indigenous knowledge systems. One strength of narrative lies in its power to foster caring, curious children who can see beyond themselves. Stories open up realms of possibility, they spark questions of “what if?” as well as “what is?”. What could be more important as we work to come together in fraught environmental and social times?

Traditional Cultural Stories

Though there are stories of this type spanning the globe, I include here only a few examples from North America. It is essential to keep in mind that Indigenous creation stories are sacred. They are not considered folk or fairy tales, nor should they be presented as models for children to compose their own origins stories.

How Raven Stole the Sun (Tlingit)

Maria Williams, Tlingit, and Felix Vigil, Apache, Pueblo

One of several picture book retellings of how the shape-shifting trickster Raven steals the sun, moon, and stars from his grandfather and brings light to the people.

The First Fire (Cherokee)

Brad Wagnon, Cherokee, and Alex Stephenson

After all others have failed, brave and tiny Water Spider uses her wits to bring back a live ember to her community. This is how fire came to the world.

Cloudwalker (Gitxsan)

Roy Henry Vickers, Tsimshian, Haida, Heiltsuk, and Robert Budd

A young Gitxsan hunter oversteps his powers and gets carried aloft by a flock of swans. He wanders through the clouds, accidentally spilling water and creating rivers and lakes in the world below.

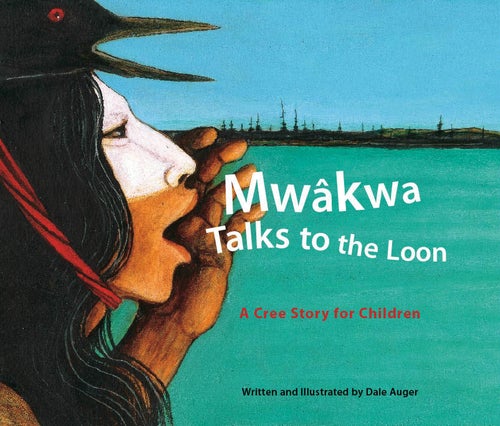

Mwakwa Talks to the Loon (Cree)

Dale Auger, Cree

A talented young hunter takes his gift for granted and loses his powers, leaving his people without nourishment. Humbled, he seeks Loon’s help and learns a valuable lesson.

Indigenous Intergenerational Stories

In these beautifully told and illustrated stories, parents, grandparents or other relatives share their knowledge of the natural world with a child. An often unspoken but deep relationship between child and adult and the use of Indigenous vocabulary enhance for the child a remarkable quality of attention to their surroundings.

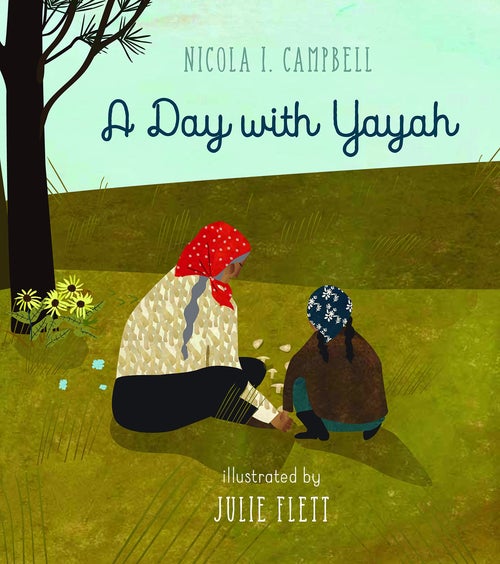

A Day with Yayah

Nicola Campbell, Salish, Metis; and Julie Flett, Cree-Metis

A family goes out to forage for wild plants and mushrooms, as the grandmother (Yayah) conveys her extensive knowledge of the land.

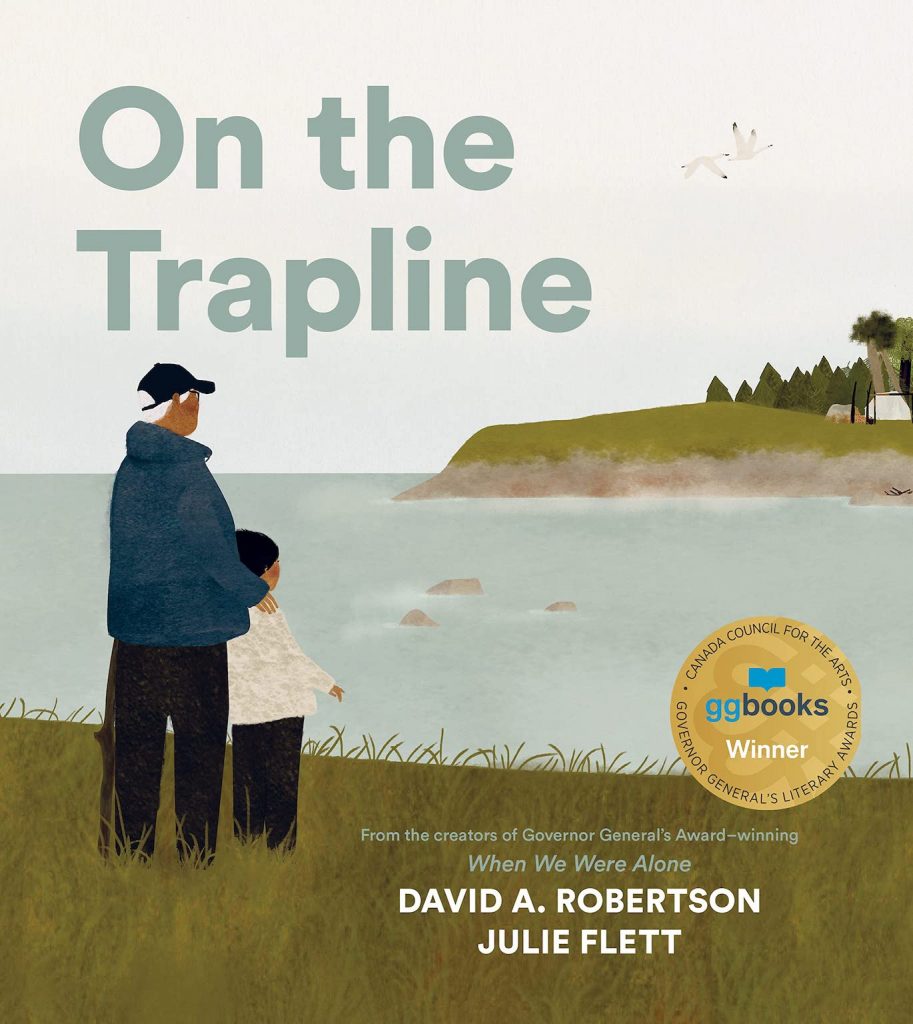

On the Trapline

David Robertson, Swampy Cree, and Julie Flett, Cree-Metis

A boy from the city visits his grandfather who takes him to his remote trapline. In an endnote to this powerfully told tale, the author writes: “Being on the trapline with my father was the most significant moment in our relationship – a homecoming for me as a Cree man and truly a journey home for him.”

Mii Maanda Ezhi-gkendmaanh (This is How I Know)

Brittany Luby, Great Lakes Anishinaabe and Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley, Great Lakes Anishinaabe; translated by Alvin Ted Corbiere and Alan Corbiere

“How do I know summer is here?” This dual language book shows a child and her grandmother exploring the world around them through the cycle of the seasons. The poetic language is spare and rhythmic; a whole other (unwritten) story about the relationship between the young girl and old woman unfolds in the stunning illustrations.

Stand Like a Cedar

Nicola Campbell, Salish, Metis; Carrielynn Victor, Salish

Children learn what it means to “stand like a cedar” as they explore the land and water around them and gather wild foods through different seasons, connecting with the teachings and traditions of their Elders.

A few examples of published Indigenous picture books, with many thanks to Krista Spence and David Osorio for sharing their ideas and suggestions.

References

Aikenhead, G. S. (2001). Students’ ease in crossing cultural borders into school science. Science Education, 85, 180–188.

Anderson, D., Comay, J. and Chiarotto, L. (2017). Natural Curiosity (2nd Edition), The Laboratory School at the Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study, University of Toronto.

Blaeser, K. (1999). Centering words: Writing a sense of place. In W. Warrior & J. Weaver (Eds.), Wicazo Sa Review. 14(2)

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Harvard University Press: MA.

Gilbert, J., Hipkins, R. & Cooper, G. (2005). Faction or fiction: Using narrative pedagogy in school science education. Paper presented at Redesigning Pedagogy conference: Singapore. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Godkin, C. (2014). Wolf Island. Fitzhenry & Whiteside.

Hooper, M. & Coady, C. (1996). The Pebble in my Pocket. Frances Lincoln Ltd.: London

Hopkins, E. J., & Weisberg, D. S. (2021). Investigating the effectiveness of fantasy stories for teaching scientific principles. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 203,

Kelemen, D., Emmons, N.A., Seston Schillaci, R., & Ganea, P.A. (2014). Young children can be taught basic natural selection using a picture-storybook intervention. Psychological Science.

Kimmerer, R. (2015). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

Korkmaz, H. (2011). The contribution of science stories accompanied by story mapping to students’ images of biological science and scientists. Electronic Journal of Science Education Vol. 15, No. 1 (2011).

Lindstrom, C. & Goade, M. (2020). We are Water Protectors. Macmillan.

Ruddell, N., Danaia, L & McKinnon, D. (2016). Indigenous sky stories: Reframing how we introduce primary school students to astronomy. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 45, 170-180.

Sharkawy, A. (2006). An Inquiry into the use of stories about scientists from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds in broadening grade one students’ images of science and scientists (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto: Toronto, Canada.

Vyam, S. & Wolf, G. (2018). Water. Tara Publishing: India