Taking children outside to observe nature in winter has its challenges, but colder weather allows curious minds to contemplate the influence of factors like temperature and atmosphere.

Feeling the cold and enduring a lengthy amount of time in the snow can make a concept such as winter adaptation relatable for even the youngest of learners.

“Children have an innate connection to the natural world no matter the temperature outside,” says Haley Higdon, director of Natural Curiosity, an organization at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education that builds children’s understanding of the world through environmental inquiry and Indigenous perspectives.

Haley recommends getting students familiar with a space before the first snowfall. “If you have an opportunity to take your kids outside before winter is here, they’ll be able to see some of the plants, insects, seeds – maybe even tracks or trails – before everything is covered with snow.”

“Having that routine already in place keeps the focus on what you’re going outside to observe rather than the excitement being about going outside for the first time,” Haley says, suggesting educators consider incorporating their winter exploration into a year-long exploration that provides the continuity needed to get kids comfortable with outdoor learning.

What follows are seven ideas for educators engaging students in outdoor learning during winter. These activities are adaptable for any type of outdoor environment, but Haley suggests teachers start by selecting a single location and observing how it changes throughout the seasons.

“Choose a spot in the schoolyard – or a local ravine or wooded area, if you’re lucky to have one nearby! As a class, decide how you will mark off the boundaries of the location that will be the subject of your class’ wintertime excursions,” she says. “It’s remarkable how much change students will notice if you carefully and thoughtfully observe the same spot over several months.”

Recommended Resources

Natural Curiosity’s second edition builds children’s understanding of the world through environmental inquiry and Indigenous perspectives.

Recommended by Natural Curiosity director Haley Higdon, The Big Book of Nature Activities is full of authentic ways to engage your students in outdoor learning.

1. Snow and life

Each winter, nature paints its pallet with a fresh white coat, creating an entirely new opportunity for students to make observations. If your class has managed to select a location to visit throughout the year, snow may make visible what went unnoticed in the Fall. If possible, block off an area that will remain undisturbed by the class or other people. Each visit, monitor the location for signs of animals or other life.

If you are restricted to the schoolyard, ask students what visits the space during the day. What visits at night? Why do they visit? How do you know they visit? If the class manages to spot larger imprints in the snow, measure their length using standard or non-standard units. Measuring the space between prints may encourage speculation about how the animal moves. Do they slowly creep along, slither like a snake, slide like an otter down a riverbank? Or do they bound like a deer or a rabbit? If necessary, have students create their own tracks – as simple or complex as they’d like.

Consider creating a bird house or nesting box to observe the types of birds (and other animals!) living in the area. This may lead to discussions around migration, including the false belief that robins migrate south for the winter. What other misconceptions about animals and winter can your class identify?

Snow technology:

Snowshoes

Educator Jason Jones shared teachings learned from animals that he learned from his Grandmother, Nancy Jones. For example, Indigenous people were inspired to create snowshoes by the movement of rabbits on top of snow.

Snowshoe lesson

The University of Saskatchewan produced a series of lessons for Grades 6-12 students that includes Aboriginal and Western sciences and technologies. In their snowshoe lesson, students are introduced to the cultural significance of the technology and explore the concepts of force, surface area and pressure

2. Snowflakes: Up close

Snowflakes on their own are fascinating. Asking why snow has its white appearance may lead to discussion about the properties of winter’s frozen precipitation. A collection of ice crystals tightly compacted into a solid mass, snow’s white appearance comes from the natural reflection of sunlight. Interestingly, when snow piles up, it can appear blue because the larger, thicker accumulation can’t retain red light.

Dr. Kenneth Libbrecht, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology (and “snowflake consultant” for the movie Frozen) studies snowflakes at the molecular level. Libbrecht is working to understand the complex process that guarantees each snowflake’s uniqueness. His website www.snowcrystals.com/ is full of some of the first close up images of snowflakes. There are also extreme close-up videos of snowflakes growing right in front of your eyes.

In-class activity

Want to make snowflakes with your students? The Ontario Science Centre has a lesson plan with instructions and an explanation of the science behind the experiment:

Understanding how snowflakes form

Dr Ken Libbrecht demonstrates how he manages to design and grow snowflakes in his lab at the California Institute of Technology.

3. Snow accumulation

The accumulation of snow is often a topic of conversation in the winter. As a class, record the daily temperature along with any snow accumulation (or melting) in the spot your class has chosen to observe. If you’re unable to have a designated spot, find a windowsill where the snow isn’t likely to be disturbed.

Use Environment Canada’s website to learn about historical forecasts in the area. Snow researchers at the University of Waterloo gather information about snow depths in different areas using information contributed by Twitter users. Students may want to contribute their findings. Visit: http://snowtweets.uwaterloo.ca/

Measuring snow depth

Students measure and compare the depth of the fallen snow over a prolonged period of time.

4. Daylight and snow

Students will notice mornings remaining darker in the winter. Track the time the sun rises and sets. For consistent data, use www.timeanddate.com/sun/ to verify the time. At a given moment, ask students to identify where in the world it’s dark and where it is light? Is there anywhere it never gets dark or never gets light? What do these locations look like?

Discuss the sun’s position in the sky. How does it change during the day? What about over a year? How do we know it’s changing? Over the winter, measure and record the height of your students’ shadows using standard or non-standard measurement. As your data accumulates, discuss why the measurement varies. Alternatively, the shadow of a vertical metre stick can be used for observation so that the object casting the shadow remains a consistent height and the changing proportions may be clearer.

The sun and shadows

A student-friendly video exploring why shadows are longer at some points during the day and shorter at others.

5. Melting snow

When snow melts, where does it go? Gathering snow in a see-through container and observe how it melts. Before the snow melts, mark the height of the snow on the side of the container and ask students what they think will happen. Encourage students to speculate why the snow is melting. Does the temperature influence change? How else is it influencing volume and mass?

When the snow has melted in the container, mark the water level. Why does the water take up significantly less space than the snow? Now, take the container back outside and bring it back in the next day. Why does the ice take up more space than the water but less space than the original snow?

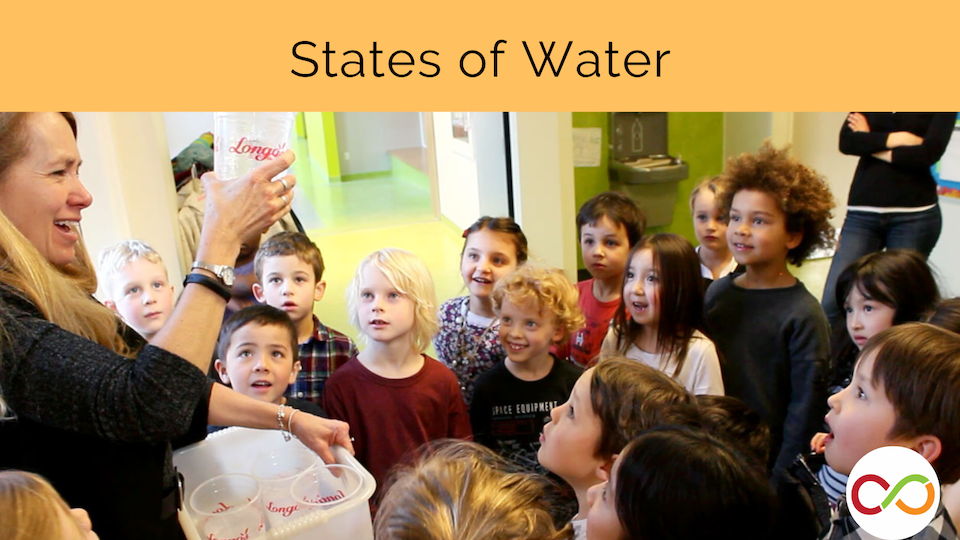

Exploring the various states of water

In this multi-part lesson, students investigate the properties of water in its liquid, gaseous and frozen states.

6. Ice Formation

A small frozen body of water, such as a puddle or the container of water used in the previous activity, can launch an investigation into ice and its influence on the environment. Invite students to observe any shapes created by trapped air frozen water. How did they get there? Why do they appear as they do? Ask students to think about any larger bodies of water they are familiar with. Do they freeze over in the winter? Students may recognize some lakes freeze over, while others don’t – or that it differs from year-to-year!

The Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory has documented Great Lakes ice cover since the early 1970s and have created an animation illustrating how vastly different ice coverage has been for the past 40 years: www.glerl.noaa.gov/data/ice/historicalAnim/

Early Years Exploration

“Kids love ice. What they learn is dependent on what they do with it,” says Krista Spence, teacher-librarian and land-based educator at the Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study. “Something like chipping away at ice and recognizing how it differs from water is an enjoyable, authentic sensory learning experience.”

7. Life and ice

When observing ice outside, is there any sign of life? Perhaps students will identify insects, larvae or no life at all – even that’s a mystery! The Smithsonian created a summary of the various insects that survive the winter and how they do so.

Discussion may lead to larger bodies of water and the life they support. Where do the fish and frogs go when winter changes their home from water to ice? Students can research the different ways various frog species have adapted to survive the winter.

Ice technology: Skates

As students begin to think about what happens to life in a frozen body of water, they may also begin to consider how humans use large areas of ice, including for skating. There are many ice skate styles, each of which is designed to achieve a different result.

How frogs survive winter

Witness a tree frog awakening after a long winter at the bottom of a pond. Its body produce urea and glycogen which act as ‘cryoprotectants’ that prevent the frog’s cells from freezing, while allowing the water between cells to freeze:

Students may be interested to know scientists continue to learn about the behaviour of fish in winter. In 2020, researchers from the University of Toronto discovered that two species of fish that don’t normally inhabit the same area seem to do so in the winter.

“While the lake trout remain active throughout the winter, the bass enter a state of semi-hibernation, slowing their swimming and eating activity. As a result, the two species aren’t competing for food even though they are occupying the same area. “It’s something we had thought was happening, but never had the data,” one of the researchers says.

Author

Zachary Pedersen

Robertson Program Manager